The Importance of Experiencing Art in Person

“So if I asked you about art, you’d probably give me the skinny on every art book ever written. Michelangelo, you know a lot about him. Life’s work, political aspirations, him and the pope, sexual orientations, the whole works, right? But I’ll bet you can’t tell me what it smells like in the Sistine Chapel. You’ve never actually stood there and looked up at that beautiful ceiling; seen that.”

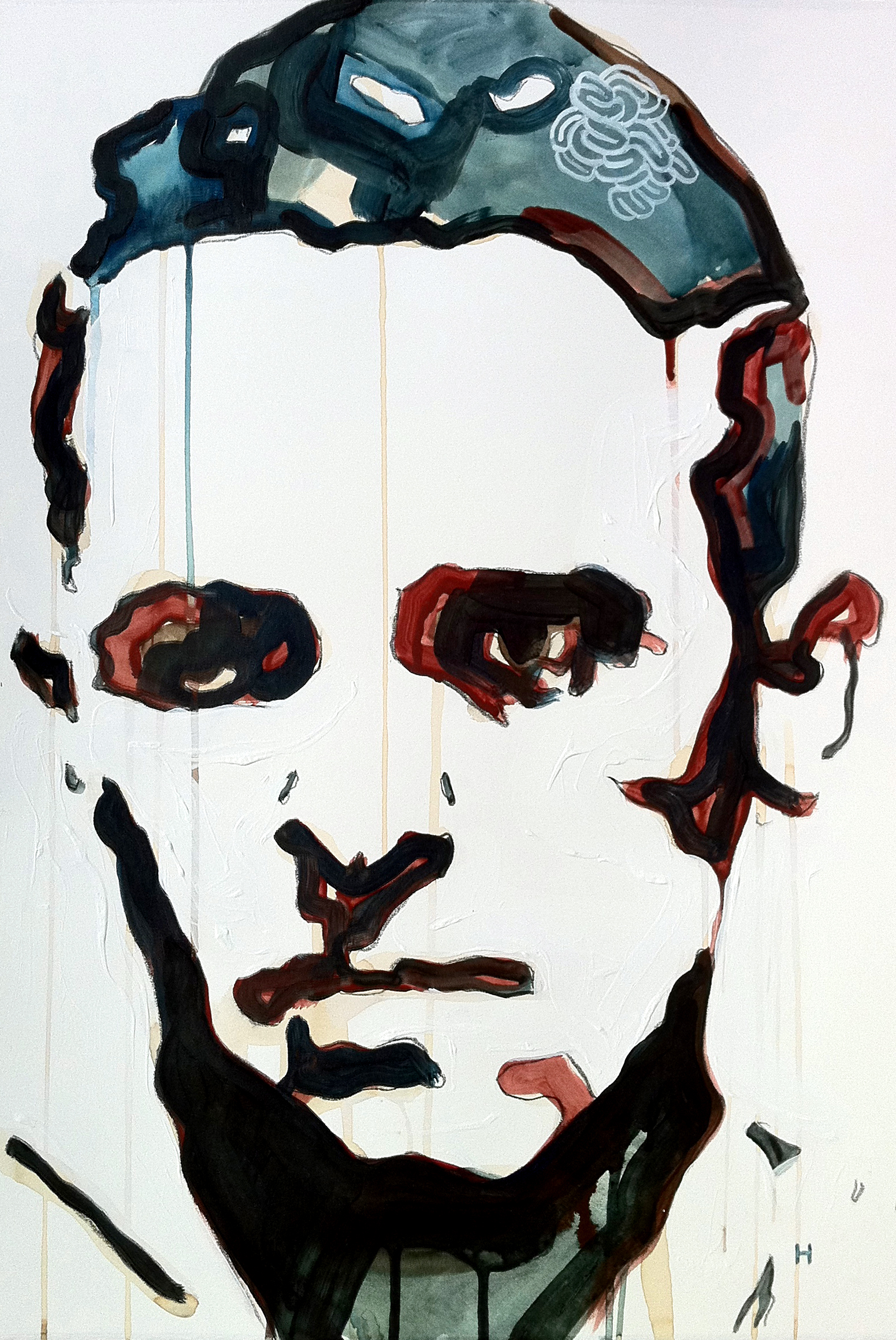

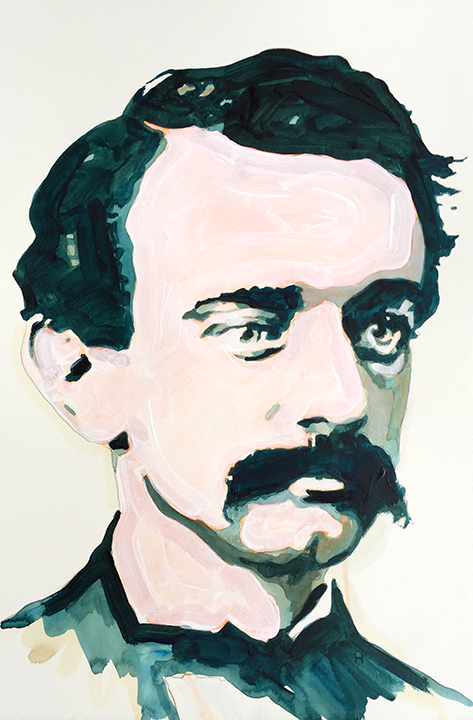

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer

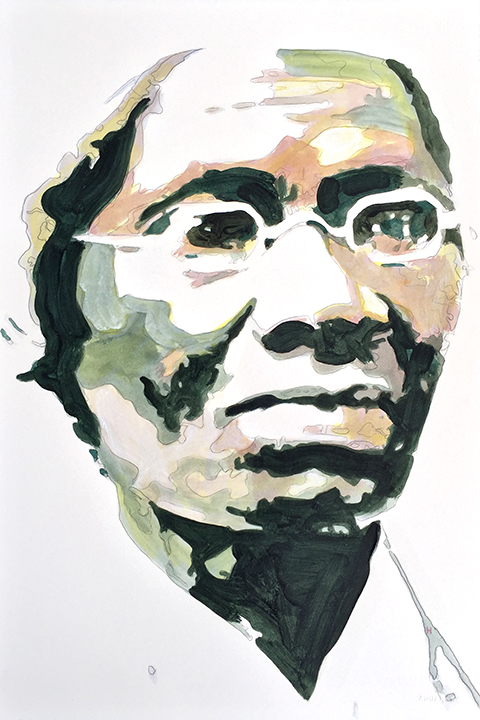

Henry Taylor

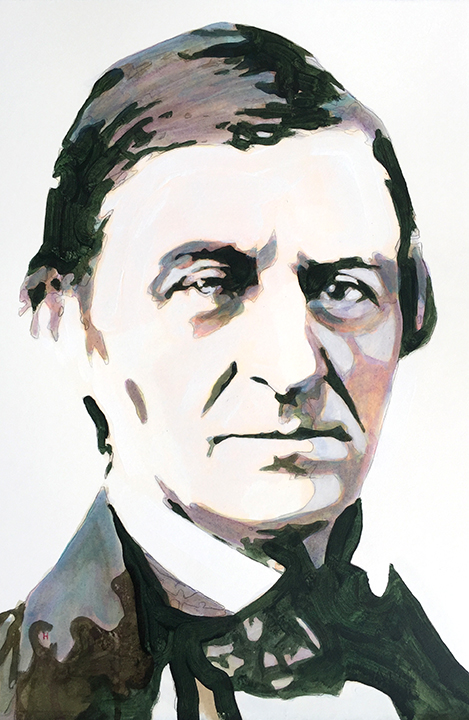

Aliza Nisenbaum

People frequently complain about Jackson Pollock. They say things like, "I don't get it" and "I could do that" or "That's just a splattered mess." Personal opinions are valid in art but my reply to those comments is always the same question, "Have you ever seen one of his paintings in person?" Because there is something visceral and overwhelming about seeing a Pollock - a two inch print in a schoolbook just doesn't do it justice. Pollock paintings have a great deal of nuance - the sheer number of colors is surprising because he's so often associated with black inky paint on raw canvas. There are fingerprints, crinkles, blurry drips of thinned paint alongside thicker ones. And there is certainly pattern, intent, and energy. Dismissing his work after seeing it in a book is like listening to Nirvana on a shitty tape deck and saying, "There's distortion and I can't understand the lyrics."

I just returned from a trip to New York - my wife and I zigzagged across the city, seeing as much art as we could cram into a few days. We went to the Whitney, the Met, Met Breuer, and MoMA - to name a few. This is not our first trip of this nature but I saw more inspiring work in a short window than any past visit. The Whitney Biennial was particularly interesting because, to me, it represented a changing of the guard - you could see the new leaders in art emerging from this grouping of contemporary artists. The attitude of the work was youthful, smart, largely figurative, and certainly more accessible than what I associate with past generations of academic artists. The highlights for me were Henry Taylor, Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Shara Hughes, Aliza Nisenbaum, and Carrie Moyer. But there is one painting in particular that caught me off guard...

I'd read several articles in advance (see links below), so I was prepared for the controversy and content of the work. Intellectually, I knew exactly what the piece was about, the artist's point of view, the public response, and I'd seen the image many times online. But when I stood in front of Dana Schutz's "Open Casket," I got emotional. I didn't cry but I did come close and that is not something that is normal for me in a museum - I'm usually the guy eyeballing the tiny details to see how the paint was applied or which materials were used. This painting was different, like touching a nerve ending or having chills shoot up the back of your neck. It packs a punch and holds you by the throat. There can be magic in art that is almost purely driven by the gut/heart/soul. Intellectualizing art or demeaning it by only focusing on content from afar is missing out on its true value to society. As Bruce Lee said, "It's like a finger pointing away to the moon. Don't concentrate on the finger or you will miss all that heavenly glory."

Hyperallergic: Censorship, Not the Painting, Must Go: On Dana Schutz’s Image of Emmett Till

The New Yorker: Why Dana Schutz Painted Emmett Till

The Washington Post: A white artist responds to the outcry over her controversial Emmett Till painting

The Guardian: The painting that has reopened wounds of American racism

The New York Times: Should Art That Infuriates Be Removed?

Blouin Art Info: Problem Painters: Dana Schutz and David Salle in Conversation

Artsy: Dana Schutz Bio & Works

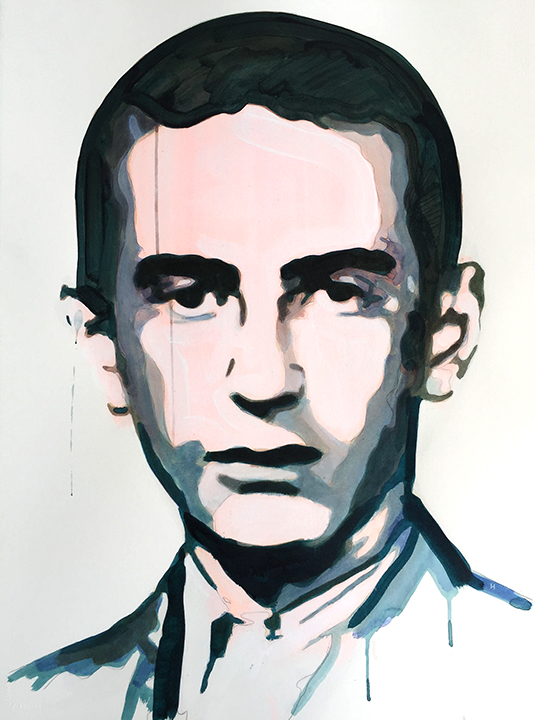

Dana Schutz

Basquiat & Relative Value

"I want to make paintings that look as if they were made by a child." - Basquiat

This week a Japanese billionaire spent over 100 million dollars on a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting: https://nyti.ms/2rxoFOx When I heard this news, I immediately thought of scenes from The Radiant Child where Jean-Michel nonchalantly walks around stepping on his paintings, which are strewn about the floor like old newspapers. And he painted with his hands, made art out of broken doors and discarded items that you might think of as garbage. He did not treat his work like precious objects and just seemed compelled to constantly create. I think he made a conscious effort to be innocent in his approach to painting. In Julian Schnabel's biopic about JMB, there is a telling quote, "Do you ask Miles where he got that note from?" - that seems to line up with the man I saw in the documentary; he believed that his job was to create and not observe, analyze, dissect, worry, or obsess.

In contrast, I am participating in a juried exhibition at Piccolo Spoleto in Charleston right now. I was at the opening last night and my wife overheard a local sculptor asking why her piece was not protected behind glass.

Just make art.